Despite the growing knowledge that food system solutions should account for interactions and drivers across scales, broader societal debate on how to solve food system challenges is often focused on two dichotomous perspectives and associated solutions: either more localized food systems or greater global coordination of food systems. The debate has found problematic expressions in contemporary challenges, prompting us to revisit the role that resilience thinking can play when faced with complex crises that increase uncertainty. Here we identify four ‘aching points’ facing food systems that are central points of tension in the local–global debate. We apply the seven principles of resilience to these aching points to reframe the solution space to one that embeds resilience into food systems’ management and governance at all scales, supporting transformative change towards sustainable food systems.

Food systems have long faced simultaneous challenges related to environmental, social and economic dimensions of sustainability 1 . The broader debate engaging both academics and societal actors on how to ‘solve’ our food system challenges tends to reduce the solution space to dichotomous perspectives. One example is the dichotomy of scale, where one narrative advocates for more localized food systems, while the opposite highlights the need for efficient coordination of food systems at the global level. While these perspectives are not always presented as mutually exclusive, they represent two main contrasting trends in the broader societal debate 2,3 .

The local–global debate is not new. Shifts to or calls for local or global food systems can be found in response to many historical food system crises 4 . However, the local–global debate is now resurfacing under drastically altered conditions (Box 1). Thus, it is timely to revisit the core tenets of the local–global debate and understand how to more constructively reframe food system challenges and solutions.

Much has been written from an academic perspective on the local–global debate 3,5 . While the evidence base is expanding, different streams of the food systems literature have traditionally been associated with different sides of this dichotomy of scale. However, a large body of research has shown that the challenges of modern food systems — including the destruction of natural resources, inequitable distribution of power, negative health impacts and rising food insecurity — are not unique to either local or global systems 2 . The line between what could be perceived as local and global is most often blurred and sometimes non-existent. For example, many production systems considered to be local depend on and contribute to global supply chains 6 . Also, ‘local’ is no guarantee for greater sustainability. Local farms may be closer to consumers, but could well be intensive systems that are no more ecologically sound than different production systems at other scales 2,7 . Thus, instead of looking for solutions in going either ‘more local’ or ‘more global’, food systems should be considered as complex adaptive systems where interactions and drivers across scales shape outcomes 8 .

Resilience, defined as the capacity to respond, adapt and transform in the face of a disturbance while still retaining the same core identity, provides an approach for understanding and managing change in complex social–ecological systems 9 . Resilience thinking acknowledges that there will always be inherent uncertainties and surprise effects when navigating current and future crises, which prevents us from relying on a priori solutions.

In this Perspective, we focus on resilience that supports sustainable, healthy and just food systems, and on what resilience would mean in the context of the local–global debate. We argue that using a resilience heuristic to diagnose food systems concerns will allow us to identify and relieve the underlying drivers of food system challenges. We emphasize that transformative pathways include changes across local and global scales working together to create resilience.

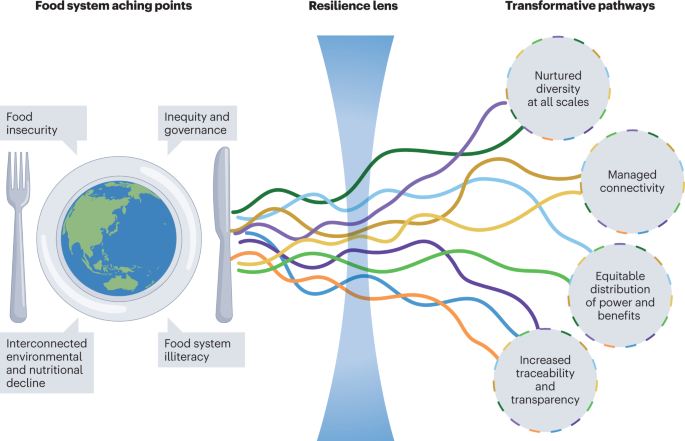

Further, we go beyond general calls for resilient food systems (that is, the capacity of a system to respond, adapt and transform in the face of change) and describe specifically how resilience could be built into food systems. We propose examples of how to embed the seven principles of resilience 9 (Box 2) into food systems at different scales to address four major ‘aching points’ or challenges that have (re-)emerged in recent years. We then propose examples of transformative pathways towards more sustainable and resilient food systems (Fig. 1).

Coronavirus disease 2019. Lockdown restrictions, widespread illness and connected economic crises at individual and national scales have threatened food security for many, particularly those already marginalized 67 . Some have called for nation states to protect food security by reducing global trade and instead boosting national production and building local governance systems that support sovereignty and democracy of localized food systems 68,69 . These voices highlight the successes of rapid local food systems innovation, and argue that these local food systems can provide a ‘new chapter’ for global food security 70 . Others have warned of the potential negative consequences on food prices and food security that could come from imposing trade restrictions, urging countries to support international governance efforts to keep global trade open, thus ensuring the movement of food to countries that rely on these imports 71,72 .

Russia–Ukraine war. The crisis in Ukraine has not only put millions of displaced individuals at risk of food insecurity. It has also once again brought to the fore the global connectedness of the food system 73 . Prolonged reductions of food and fertilizer exports from Russia and Ukraine due to the ongoing war could lead to a further 8–13 million undernourished people in 2022 and 2023, particularly in import-dependent countries 74 . While this crisis is, at the time of writing, still unfolding, there are differing views on the contribution of trade as a solution to food crises. Some argue for self-sufficiency in times of such crises 75 , and in some countries the war has led to a focus on securing local food supplies through export restrictions and hoarding of food 76,77 . At the height of export restrictions in April 2022, for example, the share of globally traded calories affected by such restrictions resulting from the war was 17% (ref. 78). Other food system actors, such as the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the International Food Policy Research Institute and the World Food Programme have warned against protectionist measures in favour of strengthening global coordination and open international trade to ensure access to nutrition for all 74,79,80 .

Intensifying environmental crises. Food production has increasingly been affected by extreme weather events such as floods or droughts 81 . While some argue that relocalizing food systems would allow for better management of resources and landscapes, others stress the importance of free trade and strong value chains as security against climate change impacts 70,82 .

United Nations Food Systems Summit. While the United Nations Food Systems Summit was a highly anticipated event that would, for the first time, put food systems at the heart of the discussion, coverage in popular media instead highlighted the divisive governance approach adopted by the Summit organizers. The organizers were criticized for distancing the Summit from the established Committee on Food Security forum 83 , recognized for integrating local voices into global food system governance, and instead putting forth ‘a narrow concept of food systems that privileges global value chains over local control and human rights 84 .’

We consider four aching points in current food systems that are central to the local–global debate. The first three aching points (interconnected environmental and nutritional decline, food insecurity and trade, and inequity and governance) address major vulnerabilities of food systems that have been highlighted by the recent crises identified in Box 1. Additionally, we highlight a fourth aching point — food systems illiteracy — that has long since been identified in the food systems literature. We anticipate that this rather slow variable will gradually reveal its importance as our food system continues to grow in complexity and evolve. We do not claim to provide a comprehensive overview of food system aching points, such as economic power dynamics or bioenergy use. For each aching point, we first present these challenges as seen through the local–global lens. We do not endeavour to present all nuances of the local–global debate, but rather those archetypal threads that have persisted over time and are particularly polarizing and paralysing in food systems debates. Next, guided by the resilience principles introduced above, we reframe each aching point through a resilience lens to demonstrate how local–global approaches create a false dichotomy of solutions. We then point to specific resilience-based measures that can help alleviate these aching points (Table 1).

Table 1 Summary of archetypal and polarizing arguments within the local–global debate and proposed strategies to reframe those arguments through a resilience lens

The biosphere is experiencing unprecedented environmental decline, and food systems are the single largest driver 10 . At the same time, most countries are currently affected by at least one form of malnutrition 11 , signalling that food systems are failing to deliver on their primary goal of supporting human nutrition. Moreover, these trends are interconnected in complex ways. For instance, rising carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere have negative impacts on the nutritional value of several crops important for food security 12 .

The dynamics of globalization are complex, but have contributed to the specialization, intensification and simplification of production landscapes at a local level 13,14 . Specialized monoculture landscapes compromise diversity and may lead to an unequal distribution of the negative impacts of food production, meaning that biodiversity loss and other detrimental environmental impacts including soil degradation and reduced air and water quality are mostly felt in exporting countries 13,14 . Global food systems are seen to lack the rich diversity of traditional local food systems, which comes at a cost. For example, biodiversity decline of crops and wild foods — non-cultivated edible species that grow spontaneously in natural habitats without need of specific management or artificial inputs — is associated with nutrient-poor diets and malnutrition around the world 15 . The simplification of landscapes — and in particular the ‘erosion’ of indigenous and traditional food crops — has impoverished communities, culturally and nutritionally 16 . It is thought that the direct connection to consumer demand for sustainable food in local food systems will drive producers to adopt more diversified, locally adapted crops 3 .

On the other hand, production for local food systems is not inherently more environmentally sustainable 3 . Other dynamics of globalized food systems can be seen to enhance environmentally efficient food production by allowing specialization best suited to local conditions 17 . This reduces environmental pressure in resource-scarce areas, such as areas facing severe water shortages 18 . Specialization and trade can also prevent overall biodiversity loss by concentrating food production in regions or nations with higher yields, thus sparing natural areas in regions with lower yields but high biodiversity 19 . In addition, global trade has diversified national food supplies 20 , which could allow for better nutrition. Finally, global food systems also allow for global standards and thereby encourage the mainstreaming of sustainable and healthy food cultures.

Diversity is at the core of resilient systems 9 . Yet food systems are currently losing diversity at multiple scales and from production to consumption, compromising both health and environmental sustainability. Thus, from a resilience perspective, the question is not whether healthy agro-ecosystems and diets are better achieved by global versus local food systems, but rather how can we encourage diversity at all scales and throughout the entire food system.

Multiple aspects of diversity need to be nurtured and targeted at all scales by management practices and governance. This includes the diversity of crops, agricultural practices and landscapes in food production systems 21 ; a diversity of livelihood options available to individuals such as farmers 22 and nutritional diversity for healthy diets and diversity of food cultures 23 .

To achieve this, the agency of key local and global actors needs to be supported, ensuring that they have the power and understanding to promote incentives, capacities and motivations supporting diversification. For example, engaging with large-scale actors (such as agri-business) can enhance their awareness and support them to become stewards and drivers of positive transformative change 24 . Governments and inter-governmental organizations have a key role in providing the right incentives to protect vulnerable smallholders. They can move from perverse subsidies supporting unsustainable farming practices to agriculture resilience bonds that allow farmers to adopt practices that enhance crop and landscape diversity 25 .

In 2021, 29% of the global population suffered from moderate-to-severe food insecurity 26 , and the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic has further exacerbated acute food insecurity. Here we focus on food availability, which is determined by production, distribution and exchange.

Global food trade can be a source of vulnerability with respect to food security, leading some to favour local food systems. For example, the food security of import-reliant countries could become threatened when the food supply is disrupted by shocks in exporting countries (see the Russia–Ukraine war example in Box 1) 27 . Further, export-reliant countries often lose their food sovereignty as they produce food to cater to foreign markets 28 and global food standards that often exclude the most vulnerable smallholders 29 . From this perspective, preventing food insecurity requires carefully managing reliance on unpredictable global food markets and volatile global food prices.

Global trade can also be a critical instrument to promote food security by increasing the availability and affordability of food and the stability of the food supply 30 . Many individuals have difficulty securing healthy, nutritious diets without global food trade 31 , particularly those living in resource-scarce areas 32 . Especially in times of food system shocks, diversified and open international trade is seen as the best way to ensure food access for all (Box 1). Thus, globalization of food systems can provide more equitable access to food. Further, globalized systems have been found to provide an ‘excellent’ buffer against local disturbances by diversifying sources of food supply 33 .

At the heart of this local–global debate is whether food systems that are more or less connected through trade will achieve greater food security. Ensuring systems are sufficiently, yet not overly, connected is a key resilience principle for any system 34 . Yet achieving this balance is known to be a difficult task. Ensuring food supply for all and at all times requires both a base level of local self-sufficiency and moderate connectivity with regional and global markets 35,36 . As the impacts of trade on food security are shown to be highly context dependent 37 , a resilience perspective focuses instead on the adaptive management of connectivity across contexts 38 .

Governance of trade systems needs to allow for food sovereignty when over-dependence on international trade creates vulnerabilities, for example, a limited number of trade partners 34 . This can be achieved by, for example, providing incentives to producers to connect to diverse markets at different scales, including the local scale. At the same time, strengthening subnational and national trade networks, including informal trade structures, can also be key to foster connectivity and secure food availability 36 .

Furthermore, the role of alternative trade structures during times of disturbance could be thoroughly considered, such as strategic agreements among trade partners to include dormant links. These are structures of international trade that could be activated in times of crisis but that would remain dormant otherwise to avoid undermining local and regional markets, for example, international food aid and national food stockpiles such as granaries. This would require shifting focus from international trade as a mechanism to increase economic profit to a more holistic perspective balancing economic and social goals as a resilience-oriented strategy for facing uncertainty.

Although equity is central to all of the aching points described above, we now highlight equity in the context of governance and decision making. Current dynamics in food systems governance heavily contribute to profound injustices in terms of access to affordable and healthy food, markets and technology that support the needs of all. These dynamics also contribute to negative environmental and socioeconomic outcomes within food systems 39 .

The consolidation of actors across the global food systems has been identified as a substantial problem 40 , for example, leading to an uneven distribution of benefits 41 . Powerful global actors may receive the greatest share of benefits resulting from contemporary food system activities 42 .

In contrast, the consolidation of actors in food systems can also allow for more efficiency-oriented value chains. This includes consolidation of decision making within food supply chains 43 , and in international governance bodies (for example, the World Trade Organization and the World Bank). Global governance structures can be used to address market failures that arise due to international challenges (for example, greenhouse gas emissions and trade) 44 . These global structures can also be justified by ethical goals, such as the goal for the international community to support one another in times of crisis 44 .

Inequitable power relations are found at all levels of food systems, meaning scale-oriented solutions miss core drivers of inequity 2,41 . In resilient food systems, power and benefits must be equitably distributed among the actors in different sectors and at different scales of the system. The resilience principles of polycentric governance and broad participation speak to equitable power dynamics at all scales 9 .

A stronger focus on equitable distribution of power and benefits in contemporary food systems must include the mapping and identification of power distribution across actors and networks at all scales, including a specific focus on the needs of the most vulnerable 45 . One way to achieve this is through broader participation in governance so that the different local and regional realities are represented. For example, trade governance must include actors from different sectors (for example, nutrition experts 46 ) and scales to ensure the desired level of connectivity through trade and account for the context-specific impact of trade on local nutrition, culture and livelihoods.

Polycentric governance structures that include broad participation of actors across scales can also be used to ensure that those with power are addressing challenges in regionally, culturally appropriate and inclusive ways 9 . Top-down governance structures have allowed actors to expropriate or lease land for their own profit. For example, expropriating common property land to afforestation programmes 47 or land grabbing by national or foreign transnational corporations in regions of Africa and Latin America 48 . Broad polycentric governance mechanisms could ensure that local communities develop regionally and culturally appropriate means to secure and distribute their land resources and the benefits of local food production 25 .

Food system illiteracy refers to the loss of knowledge across all parts of food systems and limited ability to understand and navigate the complexity of food systems 49 . This includes knowledge of where food was produced, which crops and production practices are suited to a specific context, the social and environmental impacts of production and traditional knowledge on food production and preparation 50 . Furthermore, the growing physical and mental decoupling between consumption and production leads to hidden social and ecosystem burdens 50,51 .

Global food systems can make it challenging to trace and monitor the complex connections and feedbacks of food systems 52 . Consumers generally lack information about the production, distribution, processing and labour conditions associated with the globally sourced food they buy 42 . Furthermore, the globalization of diets and production are identified as drivers of the disconnection from local sustainable production practices and healthier food cultures 40,53 . To address these problems, some have proposed to reconnect consumers, producers and other actors through localized production and consumption 54 .

At the same time, there has been an explosion of supply chain transparency initiatives 52,55 and mandatory traceability regulations, which in turn provides individuals with more information. New technologies, such as blockchain, are expected to increase transparency and information flows across the food system 56,57 . The globalization of food supply has also led to the spread of food cultures, which spice local diets with innovative technologies and innovation supporting more sustainable food production and consumption.

Although the loss of awareness of the social–ecological links between production and consumption can happen more easily in global food systems, this disconnection is also apparent at local scales, particularly in urban environments 58,59 . From a resilience perspective, food literacy can be viewed as a slow variable that shifts rather gradually. Monitoring and strengthening feedbacks that bolster food literacy and encourage learning are key resilient principles that come into focus 60 .

One way to foster food literacy is to increase traceability and transparency of food system practices across scales. The responsibility for acting on this knowledge should extend far beyond consumers. This includes the systematic monitoring of the environmental and social performance of large actors through collaborative initiatives for private sector biosphere stewardship 24 . Alternative collaborative approaches to top-down private governance, for example, certifications, regulations and standards, also play a key role in the transition. For example, Participatory Guarantee Systems 61 and Relational Supply Chains 62 can offer potential pathways to bottom-up monitoring strategies for both local and global systems. Transparency initiatives can also combine top-down and bottom-up approaches. For example, Oxfam’s Behind the Brands campaign included a public scorecard of social and environmental standards of the largest food and beverage companies 63 . The public monitoring of companies’ standards served both as a public awareness campaign and as an invitation for large actors to improve their operations.

At the local scale, communities are investing in sustainable food production practices and consumption habits to increase food systems literacy 64 . Education plays a role in supporting mind shifts and mainstreaming sustainability and health across all food system sectors, although structural and systemic changes are needed 65 . For example, education in sustainable and healthy food systems from an early age may help children to make better food choices, but education along with healthy and sustainable school meals (a structural change) helps to ensure nutrition for school children from all social groups, while at the same time promoting healthy food habits from an early age 66 .

In this Perspective, we argue that it is not possible to develop pathways towards sustainable food systems that can navigate current and future crises by taking either a local or global perspective. These dichotomous perspectives are ineffective at addressing aching points because they imply that the underlying driver of vulnerability is the scale at which a food system operates. Rather, the drivers of the aching points identified in our analysis interact and influence outcomes across scales. Reframing food system aching points through a resilience lens shifts the focus away from scale-oriented solutions and towards the capacities that need to be embedded at all scales within food systems to increase social, environmental and economic sustainability while facing increasingly uncertain times. Resilience-based transformative pathways can better equip us to achieve sustainable food systems for all, now and in the future.

The authors thank Azote for producing the conceptual figure. A.W. was partly supported by the Swedish Research Council FORMAS (grant no. 2019-01579). C.Q. was partly supported by the Swedish Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation (grant no. 2017.0137) and the FeedBaCks FORMAS/Era project (grant no. 1648401). L.D. was partly supported by the Swedish Research Council VR (grant no. 2018-02051). B.G.-M. was supported by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research innovation programme (grant no. 682472—MUSES). M.J. was partly supported by the Mistra Food Futures programme (DIA 2018/24 8). L.P. was partly supported by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (grant no. 115300) and Swedish Research Council FORMAS (grant no. 2020-00670). E.W. was supported by the Erling-Persson Family Foundation. This work was partially funded by the IKEA Foundation, project number 31002610.