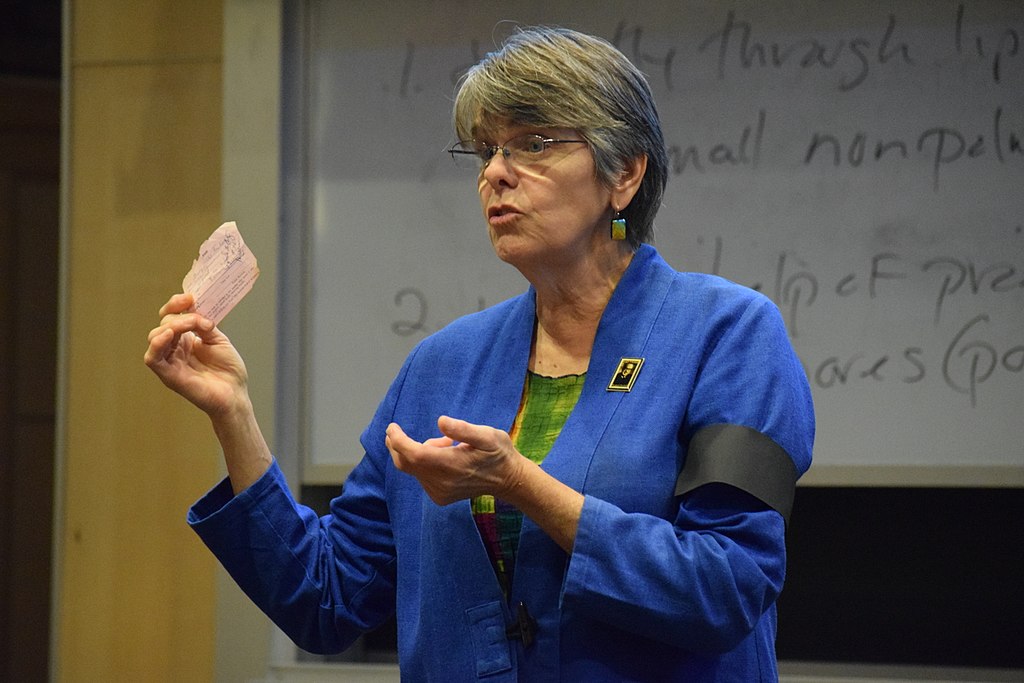

Symbolic speech consists of nonverbal, nonwritten forms of communication, such as flag burning, wearing armbands and burning of draft cards. It is generally protected by the First Amendment unless it causes a specific, direct threat to another individual or public order. Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969) was a symbolic speech case in which a school district attempted to prohibit students from wearing black armbands to protest the war. The Supreme Court held that the ban was a suppression of student symbolic expression and therefore a First Amendment violation. In this 2017 photo, Mary Beth Tinker holds the original detention slip she received for wearing the black armband. (Photo by Amalex5, CC BY 4.0)

Symbolic speech consists of nonverbal, nonwritten forms of communication, such as flag burning, wearing arm bands and burning of draft cards. It is generally protected by the First Amendment unless it causes a specific, direct threat to another individual or public order.

Symbolic speech has long been a part of U.S. history. Before the Revolutionary War, patriots would erect liberty poles protesting British governance.

The poles later became ways to protest local government regulations and taxes, with placards affixed to the poles, providing a way for a common man with little influence to protest. Federalists considered erection of poles criticizing government to be acts of sedition.

In more modern times, the Supreme Court has wrestled with symbolic speech, recognizing it as a protected form of expression.

However, symbolic speech may be more regulated than traditional forms of speech because it involves conduct or action, not simply words. The Supreme Court’s ruling in United States v. O’Brien (1968) demonstrates this point well; the standard set in this case continues to be applied.

O’Brien involved a Vietnam War–era law that prohibited the destruction of draft cards. Congress defended the law on the basis that it had a legitimate reason for protecting draft cards: They indicated draft status and other information and facilitated government-citizen communication about this status, both critical factors in a time of mobilization for war.

The Supreme Court created a four-part test to determine when regulation of symbolic speech violates the First Amendment:

The court ruled that the draft card regulation passed all parts of the test and thus was constitutional.

Also decided during the Vietnam War was Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969), a case in which a school district attempted to prohibit students from wearing black arm bands to protest the war.

The Supreme Court rejected the school’s argument that it needed the regulation to maintain order. The court held that the ban was a suppression of student expression and therefore a First Amendment violation. Critical here was the fact that students were peaceful and nondisruptive in their use of armbands as symbolic speech; wearing the armbands was no more disruptive than other symbols and jewelry that students were permitted to display.

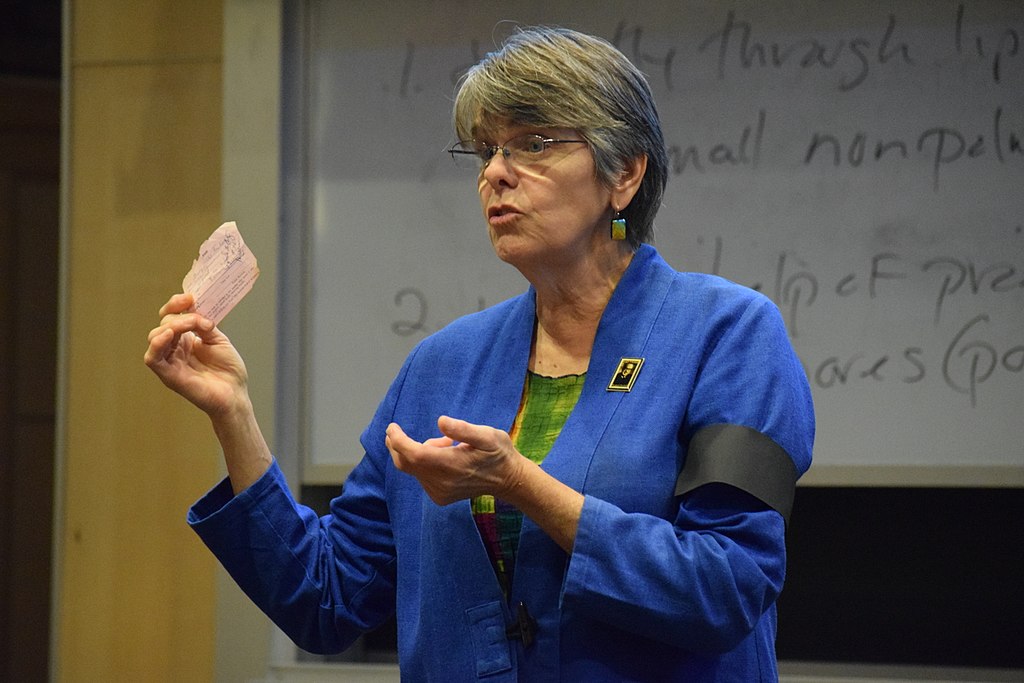

The O’Brien test, used to determine when the regulation of symbolic speech violates the First Amendment, has not been considered appropriate in every symbolic speech case, specifically in cases dealing with flag burning. The Supreme Court said in Spence v. Washington (1974) that laws dealing with flag burning or misuse are “directly related to expression in the context of activity.” In this photo, a protester throws an American flag over burning debris outside the Democratic National Convention at the Staples Center in Los Angeles in 2000. (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer)

The O’Brien test has not been considered appropriate in every symbolic speech case. One reason is the provision that the government interest behind a given regulation must be neutral and unrelated to the suppression of speech.

The Supreme Court has highlighted this point in cases dealing with flag burning, noting in Spence v. Washington (1974) that laws dealing with flag burning or misuse are “directly related to expression in the context of activity.”

The landmark case dealing with flag burning is Texas v. Johnson (1989). At issue was a Texas law prohibiting defacement of or damage to a flag with the knowledge that the defacement will “seriously offend one or more persons likely to observe or discover his action.” Though many no doubt find flag burning offensive, the Supreme Court found Texas’s interest of “preserving the flag as a symbol of nationhood and national unity” to be insufficient.

The court wrote that any interest Texas might have in banning such speech was necessarily related to the suppression of free expression, because it was tied to the content of the symbolic speech. Particularly critical was that the flag-burning law prohibited some speakers from expressing their views through flag burning, while allowing others to do just that: those wishing to dispose of old flags were permitted to burn them in “respectful ceremonies,” but those using flag burning as a form of protest could not burn them.

The Supreme Court has also addressed the symbolic burning of other objects, such as crosses. R.A.V. v. St. Paul (1992) deals with cross burning and the use of other offensive symbols that could be viewed as so-called fighting words. Fighting words traditionally have been viewed as words likely to provoke the average person to retaliation and thereby cause a breach of the peace.

St. Paul, Minnesota, passed the Bias-Motivated Crime Ordinance that banned swastikas, burning crosses, and other similar symbols when used to arouse fear or anger “on the basis of race, color, creed, religion, or gender.” St. Paul saw the ban as merely a prohibition of fighting words, which it said were traditionally not protected by the First Amendment.

In the opinion for the majority, Justice Antonin Scalia emphasized that a key problem with the ordinance was its failure to be viewpoint neutral. While those promoting religious hatred could not use the symbols, those promoting religious tolerance or even hatred based on a nonprotected category, such as sexual orientation, could use the symbols as they pleased. Although fighting words on the whole may not be protected by the First Amendment, their use cannot be forbidden only to certain groups. Though R.A.V. was a unanimous decision, four concurring justices ruled against the Bias-Motivated Crime Ordinance for a different reason. They saw the prohibition as overbroad, prohibiting not only fighting words but also much speech that although offensive was not directed toward or threatening to a specific person.

When cross burning is linked to and applied in cases of specific directed threats to individuals, cities or states can place prohibitions on it, as the Supreme Court affirmed in Virginia v. Black (2003). This case dealt with a law banning cross burning when “carried out with an attempt to intimidate.”

The court noted that laws may single out cross burning for prohibition because of its long history of use as a threat in the United States. Because the Ku Klux Klan often used the burning of crosses to relay this message, it still holds the same threat today, and is therefore not protected when it can be shown that the cross burning is being used to intimidate. In cases of intimidation, the speaker is “communicat[ing] a serious expression of an intent to commit an act of unlawful violence to a particular individual or group of individuals” and is thus unprotected by the First Amendment.

This article was originally published in 2009. Ronald Kahn is a Professor Emeritus in the Department of Politics at Oberlin College.